Major Scales and Key Signatures

Lígia Silva is a professional musician who teaches Music Theory lessons online. Find out more on her Lessonface profile.

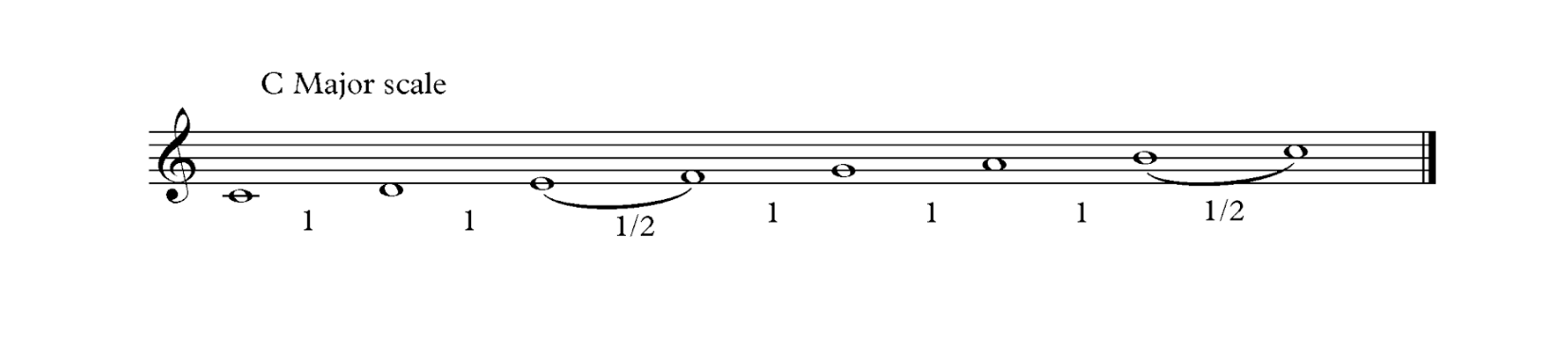

This is a major scale:

Sounds pretty familiar, right? It may seem like all notes are at equal distance from each other, but they aren’t. In fact, the distance in pitch between the 3rd and the 4th, and between the 7th and the 8th notes is half the distance of the other consecutive notes. Listen to it again, focusing on those differences. Here is how it would sound if all the notes were at equal distance:

The major scale is everywhere. The vast majority of the music heard in western countries is based on it, or on other scales derived from it. Because it is so familiar to us we don’t even feel this irregularity in the distance between its notes. In music we usually refer to this 'distance' between two notes as an interval. In the same way we measure height or weight, for instance, we can measure the interval between two notes. The unit we usually use is the tone. The smallest distance normally used is 1/2 tone (or semitone), and that’s the difference between the 3rd and the 4th and between the 7th and the 8th notes of the major scale. Between all other consecutive notes of the major scale we have a whole tone. Let us look at a C major scale:

Between E-F and B-C we have a semitone while between all other consecutive notes we have a whole tone. If you look at a piano keyboard, you’ll see that between E-F and B-C there is no black key. Here is another resource.

That happens because the interval between these notes is already a semitone, so there is no 'auditory space' to fit another note, as most of our western instruments (and our ears consequently) are usually tuned to have the semitone as the minimum interval between 2 musical sounds. Even though the voice, the string instruments and even wind instruments to some extent, can create intervals smaller than a semitone, those smaller intervals aren’t usually represented in the scales we normally use in western music.

Back to the keyboard: with the exception of the E-F and B-C intervals, the interval between 2 consecutive white keys will always be a whole tone. That's why it is possible to fit a black key between them. That black key is visually and melodically a middle point between the two notes that surround it. It can then have 2 names because it can either be considered as the left note gone higher (sharper - #) or the right note gone lower (flatter - b). For instance, the black key between F and G can both be referred to as F# (an F gone a semitone higher) or Gb (a G gone a semitone lower). Note that F# and Gb have exactly the same sound and are the same key on the piano, it’s just 2 names for the same sound.

Looking back to the C major scale. If we list the intervals between its notes we will have this melodic pattern, in tones: 1 - 1 - 1/2 - 1 - 1 - 1 - 1/2. This means that whenever we hear this interval pattern we feel that melodic sequence as an ascending major scale. This intervalic pattern not only represents a group of notes, but also evokes a melodic hierarchy established between those notes. Given the intervalic distribution of the notes of a major scale and its use through history, we are able to expect the 1st note of the scale to be more stable as a proper ending for phrases, and the 7th note of the scale as less stable and demanding some resolution.

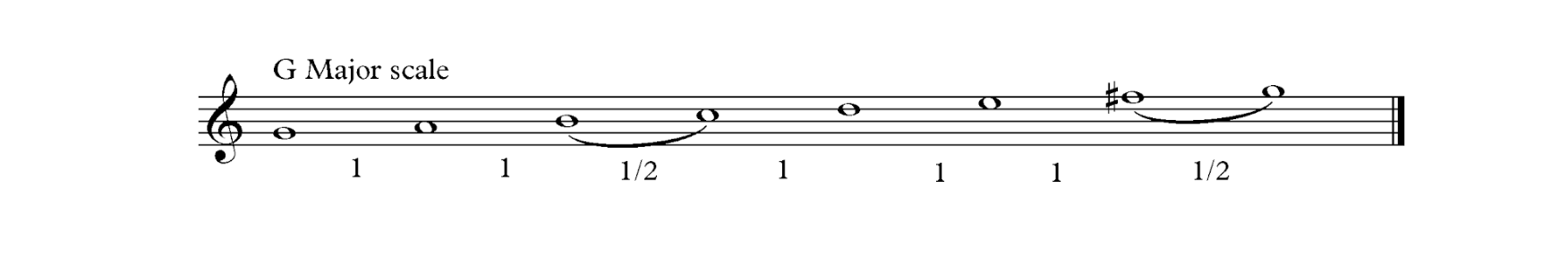

For many reasons we may want to use this pattern starting on another note besides C. It may happen due to an instrument/voice range, to the difficulty level that we want to create or even to the tone characteristics of the instrument, that may have different timbres on different notes. So let’s imagine we want to do a major scale starting on G, for example:

If we just play from low G to high G, we won’t really hear it as a major scale, although it is pretty similar.

That happens because the intervals between the consecutive notes almost match the intervalic pattern of the major scale (major scale: 1 - 1 - 1/2 - 1 - 1 - 1 - 1/2), except for the last 2 intervals. If we need the interval between the 6th and the 7th notes to be 1 tone, we have to move the 7th note higher (not the 6th lower as that would change the previous interval too). So we make the F sharp. If we play an F# (black key) instead of an F natural, we will be adjusting the last 2 intervals of the scale, and it will fit the major scale interval pattern.

All this process of bringing the intervalic pattern from the C major scale to start on G becomes easier with practice, but it still requires some thinking. The same can be done to any other note, and in some cases the thinking involved is a bit more complex. So there are other ways to more instantly know how many sharps (or flats) we have to apply to a scale to make it sound as a major scale, depending on which note we want to start playing it.

First, it is very useful to memorize the following sequence of notes in both directions:

—> F - C - G - D - A - E - B <—

We will use it in different directions for different purposes:

Scales with sharps use the ‘sequence for sharps’

F - C - G - D - A - E - B

Scales with flats use the ‘sequence for flats’

B - E - A - D - G - C - F

If you want you can easily search online for mnemonics for memorizing this. Something strange may make it more memorable, such as Flying Cats Go Down And Eat Birds. Find whatever suits you.

How do I know if the scale will have sharps or flats?

Scales with flats have a flat in the name: Eb major, Gb major for instance. So, if you want to play a major scale starting on a flat note, you know you’ll use more flats. If you start on a natural note, or a sharp note you’ll probably have sharps. I say probably because there are 2 exceptions: C Major (no flats or sharps) and F Major (has Bb, although it hasn’t a flat in its name). Now, the 2 rules:

For scales with flats:

The name of the scale is the second to last of its flats.

For scales with sharps:

The name of the scale is one note above its last sharp.

I know it sounds puzzling, stay with me, let’s do some examples to make this clear.

Let’s play a major scale starting on Eb. We use the rule for flats: The name of the scale (Eb in this case) is the second to last of its flats. Now we go to the sequence for flats:

B - E - A - D - G - C - F

and select all flats needed in order to make Eb the second to last. That means using B - E - A. Always follow the order of the sequence, of course, don’t select random flats. If you play this you’ll see it follows the interval pattern of the major scale: 1 - 1 - 1/2 - 1 - 1 - 1 - 1/2. But by using this rule we didn’t have to calculate all individual intervals.

Now, let’s play a major scale starting on B. We use the rule for sharps because it doesn’t have a flat on its name and isn’t one of the two exceptions either: The name of the scale (B in this case) is one note above its last sharp. Now we go to the sequence for sharps:

F - C - G - D - A - E - B

We need B to be one note above the last sharp. So, one note below B is A. “Below” in this context means one note lower in the score; think one note lower melodically. If A will be the last sharp, that means we will use all sharps from the sequence until A: F - C - G - D - A. In order to play a major scale starting on B we need to consider these 5 sharps.

Now I’ll leave you with 4 exercises to practice these 2 rules. The first 2 are simpler, the last 2 need you to invert the logic used here:

- What sharps or flats do I need to play a major scale starting on Db? And on F#?

- Which scale has 4 sharps? Which scale has 2 flats?

I hope this helped clear some doubts about the theory around scales, a subject that students usually find confusing. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me!

|

ABOUT LÍGIA SILVA

Lígia is a flutist and saxophonist, with professional experience on classical and jazz music. Graduate in classical flute and jazz saxophone, she studied in Portugal (ESMAE) and Belgium (Antwerp Conservatorium). With a master degree in musical education, she has been teaching kids and adults for the last 10 years. Along with a career on performance, she has done some original compositions exploring a mix of the jazz and classical genres. At the moment she is starting a PhD about the effects of music on our time perception. |

Lígia's lessons are rated five stars in 27 verified student reviews, like this one:

Lígia is a fantastic teacher, very talented and detailed oriented. She has a lot of musical knowledge and shares it with pleasure with her students.

-Igor Dutra, review from October 16, 2020