Why Does Our Musical Alphabet Have Twelve Tones?

One of my guitar students recently asked me if musical tones vary as much as the color palette does among cultures and languages. For example, all languages have words for the fundamental colors such as black, white, red, yellow, blue, and green; but vocabulary for more complex variations varies greatly. Some languages do not have words for colors like purple, pink, orange, or brown. Other languages have specific words for colors that we English-speakers would consider subtle variations. In Russian, the colors light blue and dark blue have completely distinct and unrelated words. Likewise, languages that evolved in arctic climates have many words for white derived from the various hues that snow can take on.

Let's relate this to music. If you sing or play a fretless string instrument like the violin, have you ever wondered why a note that sounds somewhere in between B and C is just an 'out of tune' B or C rather its own distinct note? If you're learning piano, guitar, or any other instrument where the notes are defined by keys or frets, have you ever wondered why there are just twelve tones? You can sing notes that are somewhere in between any two adjacent piano keys or guitar frets. Why aren't there keys or frets for those notes in between? Who decided that exactly seven white keys and five black keys make up the musical alphabet, and why?

Why Twelve?

The explanation lies in a combination of physics and culture. The twelve-tone system is not a global standard; many non-Western cultures use different tonal systems. However, some intervals – namely the octave – are present in all musical cultures. The structure, significance, and emotional interpretation of intervals within the octave depends on the culture.

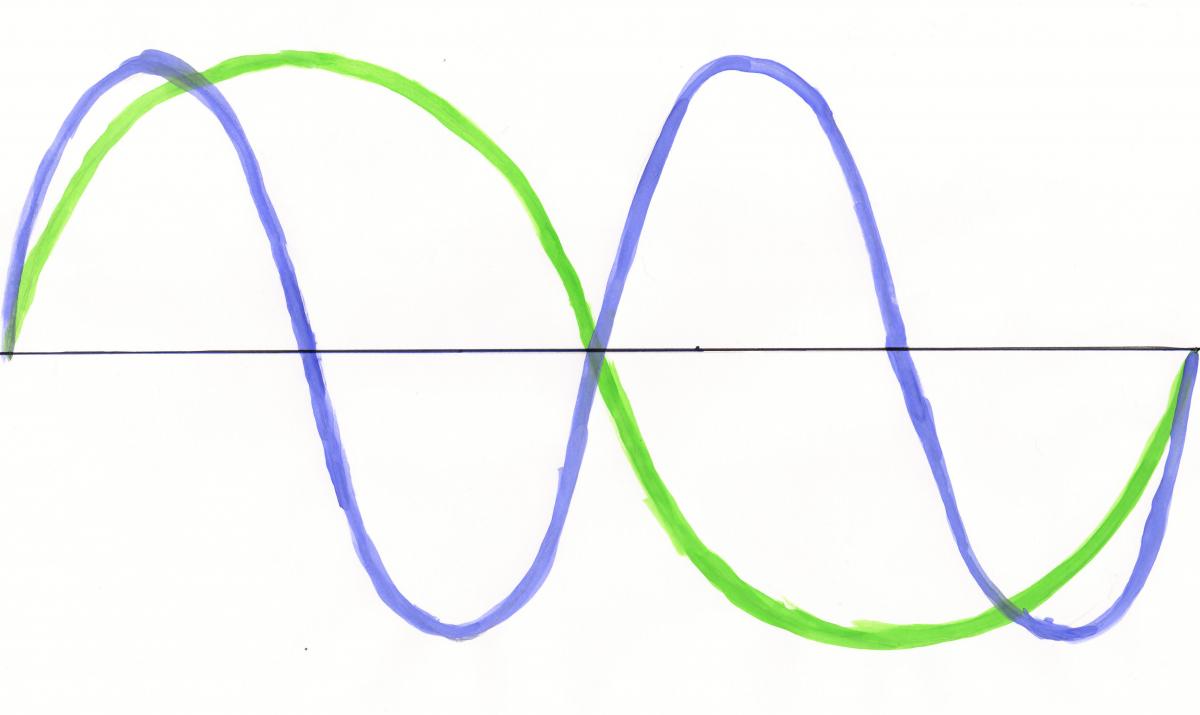

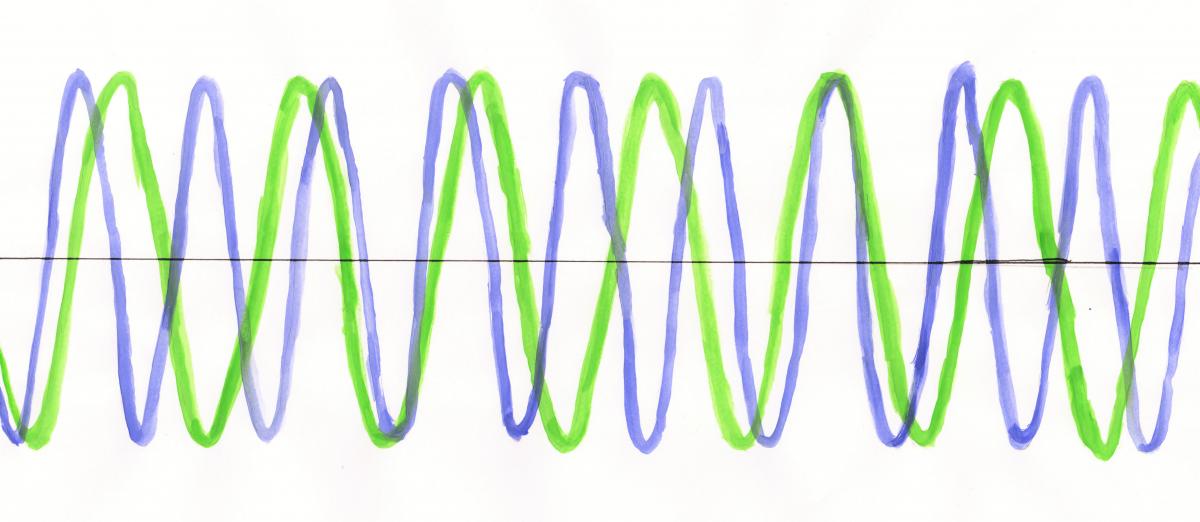

To start, musical notes sound the way they do due to the frequency of their sound wave. Higher notes vibrate faster (higher frequency), lower notes vibrate slower (lower frequency). When two waves sound at the same time, the waves can line up neatly and mathematically, and the result is pleasing to our ears. For example, in an octave, the higher note vibrates exactly twice as fast as the lower note, and they cross the middle together every one wave for the lower note, and every two waves for the higher note. The octave sounds smooth and harmonious; it’s what we call a consonant interval. Another consonant interval is the perfect fifth, whose sound waves line up every two cycles for the lower note, and every three cycles for the higher note.

When you hear two notes an octave apart, the higher note (blue) vibrates twice as fast as the lower note (green). The waves line up neatly every one complete wave of the lower note, and every two complete waves of the higher note. The result is a smooth, consonant sound that is gentle on the ears.

[lfassetembed]6100[/lfassetembed]

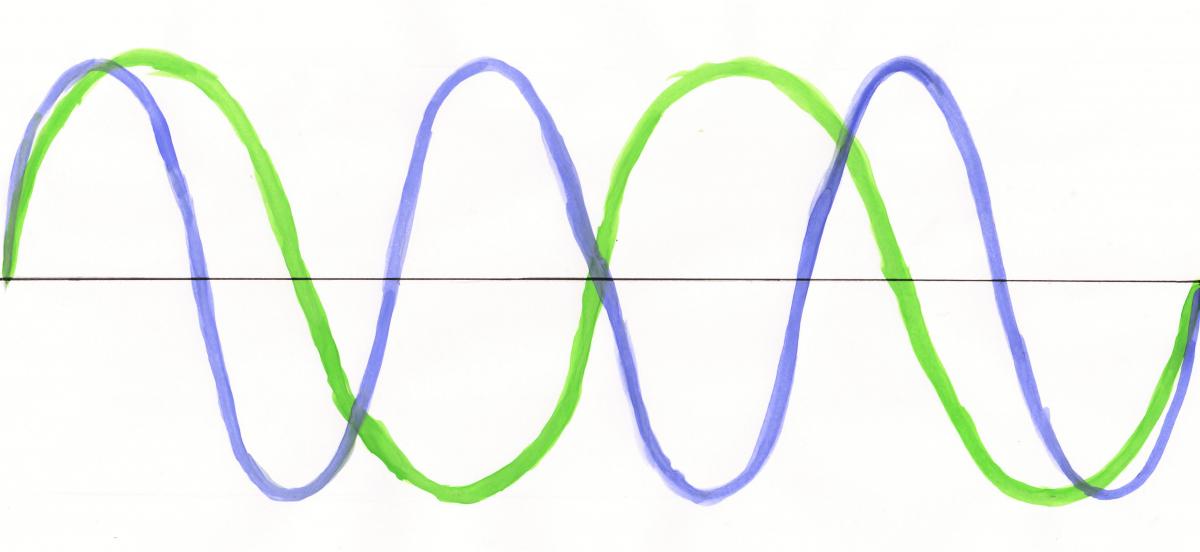

A perfect fifth is another consonant interval. The higher note (blue) completes three wave cycles for every two complete cycles of the lower note (green).

[lfassetembed]6101[/lfassetembed]

One of the most common scales throughout the world is the pentatonic scale, which contains five notes. Pentatonic scales are found in Celtic music, Eastern European folk music, Chilean music, African music, Native American music, children's songs, ancient Greek music, jazz, blues, and rock, just to name a few. There are many kinds of pentatonic scales, but the five notes usually have consonant relationships to each other. For example, listen to the major pentatonic scale (audio below). Beginning improvisers typically start out using the major or minor pentatonic scale, because it's hard to play something that sounds bad when you're using mostly notes with consonant relationships. It's no coincidence that these kinds of pentatonic scales are everywhere – human ears are naturally drawn to clean ratios of sound waves.

[lfassetembed]6102[/lfassetembed]

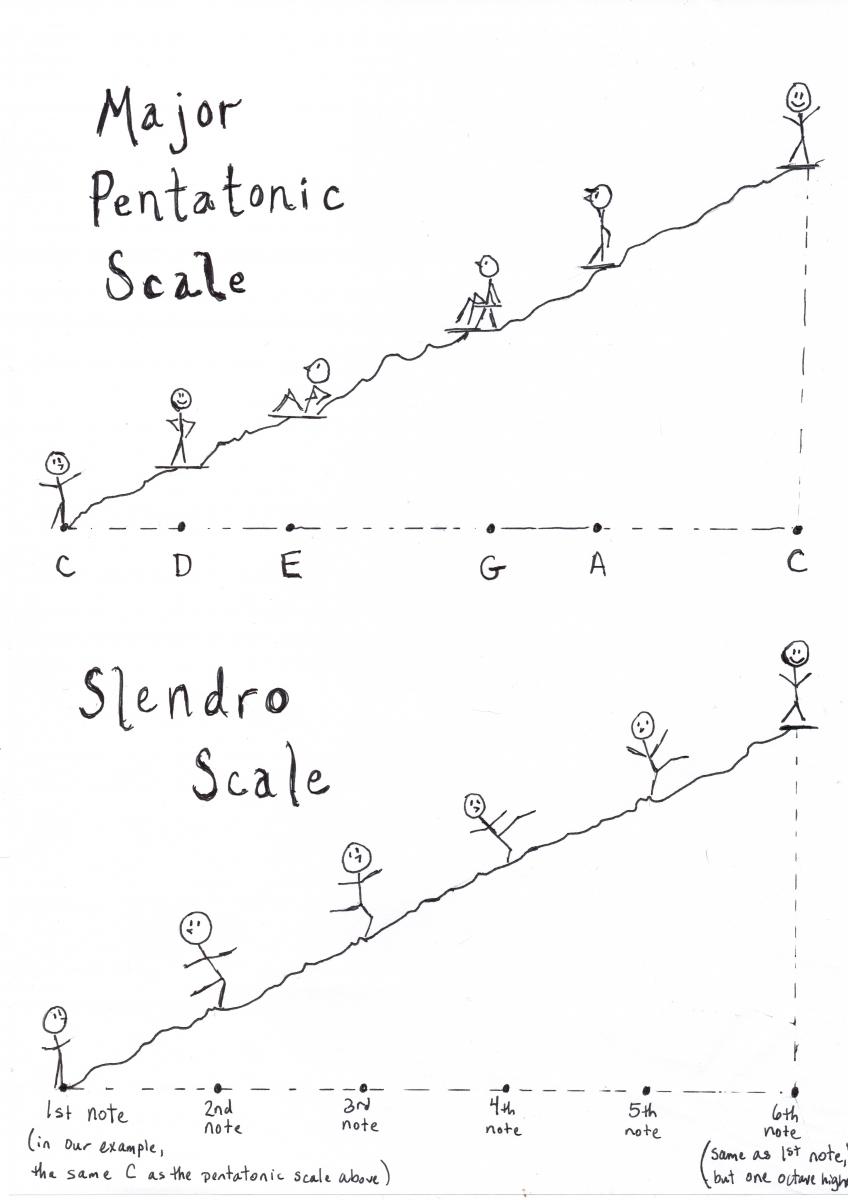

This is a C Major Pentatonic Scale. Its notes—C, D, E, G, and A—have consonant relationships to each other.

But there are many more intervals whose sound waves do not line up so neatly—we call these dissonant intervals. The tri-tone a prime example of a dissonant interval. Listen to it (audio below) and note how harsh and grating it sounds. The frequencies of the two sound waves are such that they never meet at the center.

[lfassetembed]6103[/lfassetembed]

The sound waves of a tritone do not line up neatly, so the interval sounds harsh and dissonant.

In Western music – the music that developed in Europe and North America over the past several centuries and was heavily influenced by pioneers like Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven – dissonance is equally important as consonance. The push and pull between dissonance and consonance creates and releases harmonic tension, and that gives the music a sense of motion and development. The twelve-tone system works really well for this because it contains consonant intervals like perfect fourths and perfect fifths, as well as dissonant intervals like tri-tones and minor seconds (play any two adjacent notes on a piano, that's a minor second). We are so used to the tension and release of the twelve-tone system that it's hard for us to imagine music any other way!

Yet, plenty of cultures use more than twelve tones, or different notes altogether. Furthermore, many musical cultures don't rely on consonance and dissonance to create tension. Check out a very different-sounding pentatonic scale used in Indonesian music, called a slendro scale (audio below). It's a kind of pentatonic scale because it has five notes, but besides that it has little in common with the major and minor pentatonic scales. There are many variations of the slendro scale, and tuning varies among different regions and even among different ensembles. But to our ears, all give the impression of being odd, haunting, or just plain out of tune.

[lfassetembed]6104[/lfassetembed]

The Indonesian slendro scale uses the octave to mark its beginning and end, but it doesn't center around consonant intervals. Instead, its five notes are spaced equally throughout the octave. It sounds very strange to our ears.

This particular slendro scale begins and ends on the same notes as the major pentatonic scale that I recorded. However, rather than being centered around the consonant intervals like the perfect fifth within an octave, the slendro scale uses evenly-spaced intervals throughout the octave. It's very mathematical in a sense: it's like taking five steps of exactly the same size to get from one point to another. But it's not so mathematical in the sense of sound wave ratios. Mathematical in the sense of sound wave ratios (like the major pentatonic scale) would be like taking five steps that let you land in comfortable spots, regardless of the size of the steps.

A major pentatonic scale uses notes that are 'comfortable' to land on in terms of sound wave ratios. The slendro scale uses notes that are evenly-spaced throughout the octave.

Many more musical cultures have unique tonal systems that rely less (or not at all) on harmonic consonance and dissonance. I chose Indonesian music as an example solely because I have some expert colleagues who could explain it to me first-hand. How, then, do these other systems create and release tension? After all, music without tension and release is, at best, directionless and boring. The musical cultures that don't use consonance and dissonance use a wealth of other tools to give their music vitality. Indonesian music builds tension largely through dynamics and tempo changes. Other common tools for building tension are: rhythmic syncopation or contrast, repetition of a particular idea, moving slowly towards a lower note or higher note, using pitch extremes, and contrasting colors of sound. Good musicians of any style make use of lots of different tension-building techniques. Western music's view of harmonic tension is just one particularly well-developed and specific tool that is ingrained in our ears from the time we're born. Start exploring music from various corners of the world and you'll open your ears and mind to new ways of listening to and thinking about music!